In 1993, BikeTours.com president Jim Johnson—then a freelance travel writer—went on his first European bicycle tour, along the Tauern Bike Path. Jim was also researching the origins and legend of “Silent Night” for an article for the Los Angeles Times. He planned the ride to include key waypoints (all within a day’s riding distance of Salzburg) in the lives of organist Franz-Xaver Gruber and Father Josef Mohr, who composed the music and lyrics in 1818.

In 1993, BikeTours.com president Jim Johnson—then a freelance travel writer—went on his first European bicycle tour, along the Tauern Bike Path. Jim was also researching the origins and legend of “Silent Night” for an article for the Los Angeles Times. He planned the ride to include key waypoints (all within a day’s riding distance of Salzburg) in the lives of organist Franz-Xaver Gruber and Father Josef Mohr, who composed the music and lyrics in 1818.

Jim wrote the following article for the Los Angeles Times, not knowing that a decade later he would found a company that would send more than 20,000 travelers on bicycle tours around the world, and more than 300 travelers on the Tauern Bike Path itself.

On Christmas Eve, crowds will pack the narrow knoll outside a small chapel in Oberndorf, Austria. In nearby Hallein, the church square will fill, all gazes directed at a lone gravesite. Shortly after 5 p.m., the sounds of a familiar melody will lift across the countryside. This year marks the 180th anniversary of the first singing of “Silent Night,” and many Austrian towns and villages will celebrate the event and honor its composers with concerts and sing-alongs.

While hordes of tourists flow through Mozart’s birthplace and crowd buses for “Sound of Music” tours, relatively few connect the Salzburg area with the famous carol. Even outside the holiday season, a self-guided “Silent Night” tour makes sense for interested travelers. Visits to sites connected with the carol deepen the carol’s meaning and offer both a realistic view of modern Austria and a strong sense of 18th-century life.

Before the tour, a brief history. It was just two days before Christmas when the organ bellows rotted through at St. Nikolas Church in Oberndorf, 11 miles north of Salzburg. Knowing his congregation’s love for music at midnight mass, the young parish priest took a poem he had written two years prior and asked the church organist and choirmaster to set it to music that the two could sing with guitar accompaniment.

The organist returned to his study over the schoolhouse in the neighboring village of Arnsdorf, where he gazed out the window onto the peaceful, snow-blown fields. He read the poem for a few moments and started to hum slowly, then sing: “Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht…” (Silent night, holy night…).

A few hours before mass, he made the trek back to the church, where the two men practiced the hymn and taught the refrain to the choir. Shortly after midnight on Christmas Eve, 1818, with organist Franz-Xaver Gruber singing bass and Father Josef Mohr singing tenor and accompanying on the guitar, the world heard the touching melody and words for the first time.

First Stop: Salzburg, Mohr’s Birthplace

Our tour starts in Salzburg, where Josef Mohr was born out of wedlock and into poverty on December 11, 1792, the son of a seamstress and a military deserter. Mohr’s childhood home stood at Number 31 Steingasse. It was damaged during World War II and replaced by a more modern building on the well-preserved medieval street.

Distinguished only by a small plaque, the building is nestled between the right bank of the Salzach and the 2,100-foot Kapuzinerberg in the “new” city, that part of Salzburg built primarily after the 16th century. It’s likely that young Josef escaped the poverty of his youth by climbing the narrow, stepped walkway that enters the Steingasse beside his house and weaves through medieval fortifications to the Capuchin friary atop the mountain.

Here, Josef (and today’s traveler) could look out upon the riches of Salzburg and beyond into Bavaria. The view across to the old city on the left bank is postcard-perfect and has changed little in the past two centuries. The Hohensalzburg fortress, finished in 1681 after six centuries of construction, dominates the panorama, towering over the baroque spires of the city.

Mohr could reach school or church in the old city each day in minutes by crossing one of many bridges to the left bank. It’s easy to retrace his steps. The shortest route to the massive renaissance cathedral—or Dom—where he sang and was later ordained, would have taken him across the river, past the 15th century town hall and Mozart’s birthplace (not celebrated as such until decades later) on the Getreidegasse, the most famous of Salzburg’s many narrow medieval alleys.

From there, he would have walked through the wafting scents of the old market—still active today—and past the Residenz, palatial home to the ruling archbishops, into the Domplatz to the cathedral.

It’s only a few more steps to the adjacent St. Peter’s cloister, where Mohr celebrated his first mass. Rebuilt in the 17th and 18th centuries in baroque style, the cloister church borders ancient Christian catacombs and a cemetery where Mozart’s sister Nannerl is buried. The cloister also houses Austria’s oldest restaurant, the Peterskeller, established by Benedictine monks in 803 and frequented by Mohr.

It’s an invigorating climb from St. Peter’s up winding pathways to the top of the Mönchsberg, the 400-foot high hill that stretches from the Hohensalzburg nearly two miles along the old city. (Other options to the top include a funicular railway and an elevator.)

The walk is rewarded with commanding views of the Alps to the south and the old and new cities and Kapuzinerberg to the east. To the north, the Salzach glimmers as it makes its way downstream to Oberndorf, where Mohr moved in 1817 to serve as assistant pastor at St. Nikolas.

Stop 2: Oberndorf

Mohr traveled to his new assignment by ship, a common means of transportation in 1817. Today, a local narrow-gauge railway offers a less precarious option to the small town, although many summertime tourists rent bicycles and follow a bike path along the riverbank.

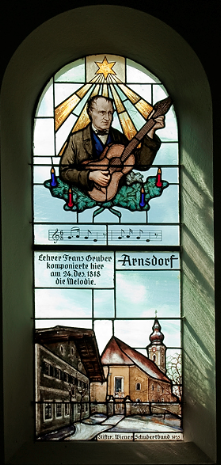

The old church where Mohr served fell to floods nearly a century ago, but the Stille-Nacht-Kapelle, the small memorial chapel completed in 1937, stands on the site. Inside, candles flicker and fresh flowers lie before a wood-carved nativity scene and altar. A guest-book reveals visitors from around the world. Light filters through two stained glass windows, one depicting Mohr and the old church, the other Gruber and the Arnsdorf schoolhouse.

The “new” church, down the street and behind a brass memorial to the two men, contains statues and altar paintings from the original church, while the nearby town museum houses a new exhibit dedicated to the carol.

Stop 3: Arnsdorf, home to Gruber

It’s minutes by car or bus, an hour or so by foot to Arnsdorf, still a tiny village consisting of a church, a schoolhouse, and a dozen homes surrounded by farmland. Gruber took his first teaching job there in 1807, living upstairs with the first and second of his three wives. His first joy, however, was music—he played guitar, violin, and organ—and he shared his love for it every day with the young farm children.

The musical spirit still lingers. On a recent visit to the schoolhouse, the sounds of children singing Austrian folk songs and the rhythmic strumming of a guitar echoed down its hardwood floors and white plaster walls. Except for nylon parkas draped on wooden pegs, the year might have been 1818.

The private apartment that served as Gruber’s home now houses a museum with furniture from the early 1800s, many of it Gruber’s own. The small bed, a guide points out with a wink, may explain why Gruber had 12 children. Entering his study, visitors can stand behind the schoolmaster’s desk and look out over the fields. Sitting at this same window, Gruber must have seen a similar scene of tranquillity and joy as he first sang the melody of “Silent Night.”

Stop 4: Hallein, Gruber’s home and grave

In 1833, Gruber took a position at the 13th century Dekanats Church in the larger town of Hallein, about 10 miles south of Salzburg. A short walk from the town center (following signs “Zum Grubergrab”) passes tall, well-kept 17th and 18th-century houses along open squares and narrow, cobblestone streets.

A small plaza fronts the plain house where Gruber lived and died. Although the church cemetery was moved, Gruber—who died in 1863 at the age of 75—still lies at peace between the house and the church in the original family plot; a wrought-iron cross marks the grave. Several years ago, the town restored Gruber’s apartment and turned the home into the Gruber Museum.

Stop 5: Wagrain, Mohr’s last years

Franz-Xaver Gruber’s story ends in Hallein, but the tour continues 20 miles southward to the village of Wagrain, where Josef Mohr served for 21 years as parish priest until his death in 1848. During those years, Mohr championed the causes of the disadvantaged, the young, and the elderly.

Behind the church, farmhouses perch on distant hills. Late one night, just before Christmas, Father Mohr was summoned there to give last rites. While returning, the 55-year-old priest became snowbound for several hours. He fell ill and died four weeks later of a lung infection.

“Silent Night” passed to the world thanks to the organ builder who came to repair St. Nikolas’ instrument. He heard about the carol, learned it, and carried it back to his home in the Tirolian village of Fügen not far from Innsbruck, nearly 200 miles away. The following Christmas, it was performed by two family singing groups (fore-runners to the Von Trapps), who later toured Europe, England, and Russia with the song in their repertoire as a “Tirolian folksong.”

One of the groups brought the song to America, performing in New York on December 24, 1839. It wasn’t until 1854, six years after Mohr’s death, that the two composers received credit for their work. Fügen has commemorated its role in starting the carol’s spread across the globe—it’s been translated into nearly 200 languages—by marking the homes of the organ builder and both families and setting aside part of the village museum.

Learn more about the Tauern Bike Path, or e-mail a tour advisor today to learn how you can explore it on bike.

Featured destinations, Self-guided, Austria

Linda Arbaugh

4 years ago

BikeTours.com Staff

4 years ago

Jim Johnson, Founder and President

Glenna Christensen

4 years ago

BikeTours.com Staff

4 years ago

All the best,

Jim Johnson, Founder and President